Of this (and little else) I am certain: there are no words quite up to the task of adequately describing how you may feel when watching The Birth of a Nation.

My guess is you will be apoplectic.

Remember that feeling you had in Braveheart when William Wallace's bride's throat is nonchalantly slit by an English soldier? When Wallace—in a daze—rides slowly into the English soldiers' encampment with only tunnel-visioned vengeance on his mind? That feeling you had at the end, when Wallace was tortured and quartered in the public square, derided by bloodthirsty townsfolk?

That pretty much sums up the way you'll feel throughout most of The Birth of a Nation.

So angry and hollowed out that you'll have a hard time focusing on any one thing.

If you have a pulse, and any empathy whatsoever, you will be gnashing your teeth by the end...at the thought of so many injustices perpetrated, one man against another, through the blight of institutional slavery. At the means, at the ends, at everything in between.

Acts II and III, tough as they are to watch with a soda in your hand on a Tuesday night, represent only a scintilla of what has actually occurred throughout time. And that's a truth that's pretty dang hard to incorporate into one's psyche. Yet here we are, 2016, and it oftentimes feels as though progress hit a wall about one-half-century ago. Whether discussing the recently opened National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., or the forthcoming Memorial to Peace and Justice in Montgomery, AL, or the forthcoming From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration museum, writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, activist Bryan Stevenson, and Senators Tim Scott (R, SC) and Cory Booker (D, NJ) remind us in stark and sobering language that "the struggle continues, and without atonement and reparations, America can not and will not heal." An unstitched lash that may remain open and infected forevermore.

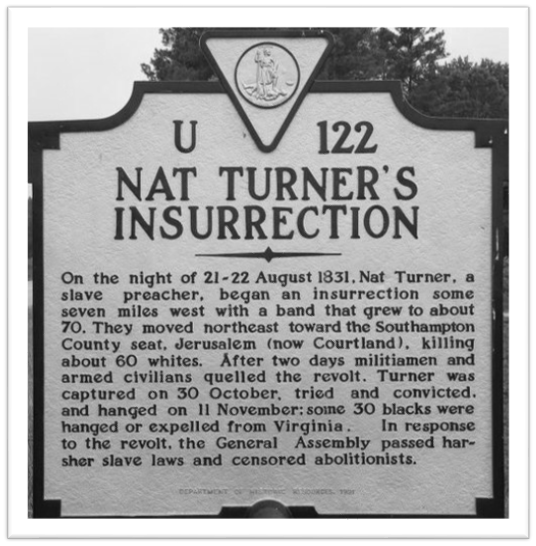

You will rightly be incensed, though entirely unsurprised by the content of The Birth of a Nation, as it is no mystery. Quite the contrary, it is a dramatic retelling of the factual events we remember from mid-school's "Nat Turner's Rebellion," aka "The Southampton Insurrection of 1831." It is a part of America's collective history, and a perfect illustration of two wrongs not making a right.

* * *

I am disappointed the film has only generated $11M in box office revenue since its debut one week ago. Adding insult to injury, the film has exited most major markets after just 5 quick days, in no small part due to (1) a rather incendiary, divisive marketing campaign, (2) Nate Parker's unhelpful appearance on 60 Minutes this past Sunday, and (3) the inconvenient dredge surrounding a 1999 rape trial in which Nate Parker was acquitted while The Birth of a Nation's co-writer, one Jean McGianni Celestin, was convicted.

In 2012, the men's accuser committed suicide. Her brother and sister have been on every single media outlet I have seen in the past week.

It is a tragedy all the way around, with no clear accounting of the facts.

Whichever way it unfolded in 1999, The Birth of a Nation is doomed, lost forever. A microscopic footnote in movie-making history, less impactful than Marlon Brando's no-show at the '73 Oscars.

Few more will see the film now, and any illusions filmmakers might have had about Oscar nominations are precisely that: illusions.

Nate Parker devoted 2009 through October 2016 to bring The Birth of a Nation to life.

Controversy killed it in less than a week.

It's bitterly ironic that a film—the sort intended to bring us together—was in large part undone because its divisive writer and director behaved, as 60 Minutes said, "unapologetic about his past, whatever his complicity in it."

Unapologetic about complicity in the past.

Huh. That sounds familiar.

* * *

Ten months ago, when The Birth of a Nation won Sundance's Dramatic prize(s), I was really excited about the film. Today, for reasons I cannot quite articulate, I feel a bit guilty for having seen it at all, unsure whether I've supported an important (if inflammatory and ambivalent) story that deserves telling, or aided and abetted a rapist whose actions led to a college student's death.

We'll probably never know what happened one night in 1999, but we do know what happened on October 7, 2016: a movie, once a critical darling, opened and no one came.

A tree, fallen in the woods, with nary a sound.

A story, hitherto told dryly and only through textbooks, re-made beautifully for big screens that would not play it.

And beyond local lore and ancestors who remember it well, all that remains in Virginia is a teeny tiny little sign beside a field, a field largely unchanged for 185 years.