Billed as "An examination of the research by forensic psychiatrist Dorothy Otnow Lewis who investigated the psychology of murderers," Crazy, Not Insane is interesting but, in the end, unconvincing. Such is the story of a few nooks and crannies in her public life, too, particularly when testifying as an expert witness in murder trials.

Dr. Lewis herself is an impressive specimen: Compact, vibrant, and full of fight and life, though not quite as mighty as, say, RBG, but in that vein, yes. Far more maternal, to be sure. Gentler, warmer, huggier, and big brown eyes perched above a tiny, gravity-defying elfin nose. The warmth, tenderness, empathy, belief and trust she doles out when sitting across from men who have killed 11 to 20+ human beings is, quite frequently, jarring to the senses. She squeezes serial killers' shoulders affirmingly, rests her tiny hands on their oar-sized shovel-shaped hands kindly, and squeezes their arms like Mom at breakfast when she wants to cajole someone into fessing up or speaking freely, perhaps by even inducing sing-song hypnotic states. At maybe 5' 2" tall, it blows my mind that she doesn't elect, instead, to sit across a steel table bolted to the floor or on the other side of handcuffs and ankle bracelets, but no, she just sits there in 10' x 10' locked rooms knee-to-knee with unbound men possessing nothing left to lose and everything to gain by similarly deleting her life as some perverse swan song before departing Earth's door stage right, just beyond the electric chair over there. Nevertheless, she perseveres, percolates, smiles, and continues to launch her charm offensive to coax killers out of their porcupine shells to recall prior abuses, the overwhelming majority of which are abundantly horrific in and among themselves. "Hurt people hurt people," and boy howdy, if someone is defiled as an object up through early adulthood by parents, step-parents, aunts, uncles, siblings, neighbors, and other ne’er-do-wells one’d think he could trust in life, you can imagine what said someone may seek to do alone in the woods two decades later.

Dr. Lewis is a pioneer and tremendous scholar, one whose rise to fame was meteoric following several notable Supreme Court cases citing her work and one life-changing TV interview with Diane Sawyer that made her a household name, but she is also a controversial figure who has endured four decades of derision, skepticism, dismission and doubt, typically after diagnosing dissociative identity disorder (DID) or neurological [brain] damage as causes for why regular folks do irregular things.

Bill O'Reilly, of course, took her to task eons ago regarding evil, which she counters is a religious concept rather than a scientific reality. Their exchange made me miss the late psychiatrist M. Scott Peck, as his People of the Lie makes a rather compelling case to the contrary. I guess it really comes down to What do you mean by 'evil,’ Where did it come from, and When?

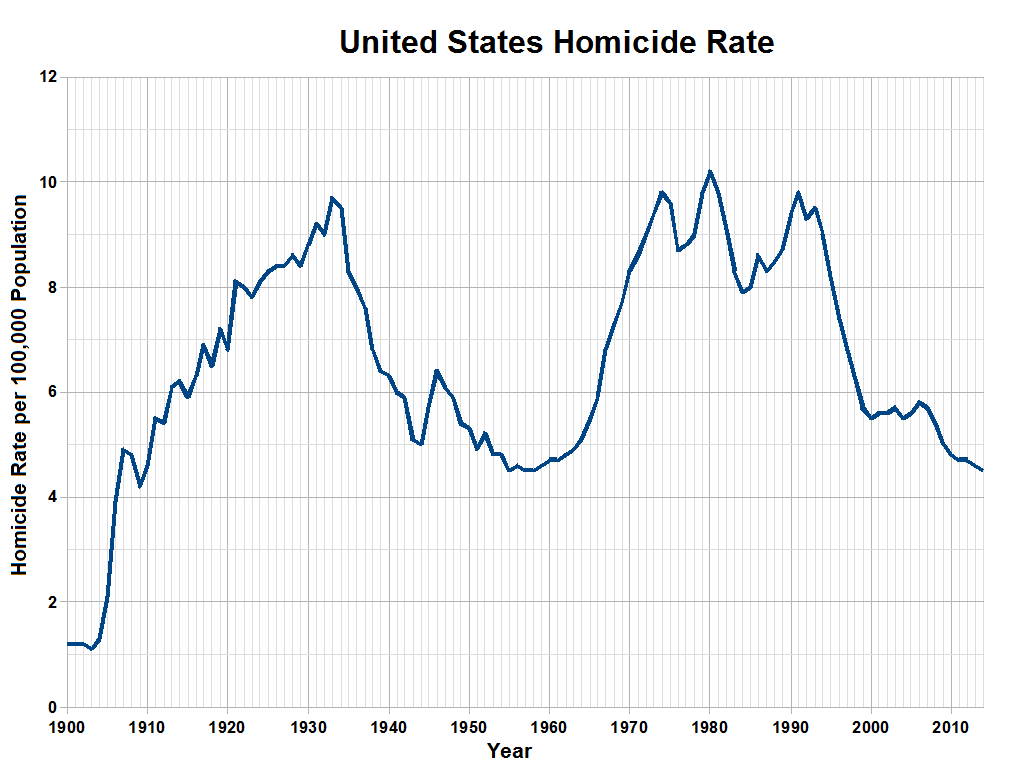

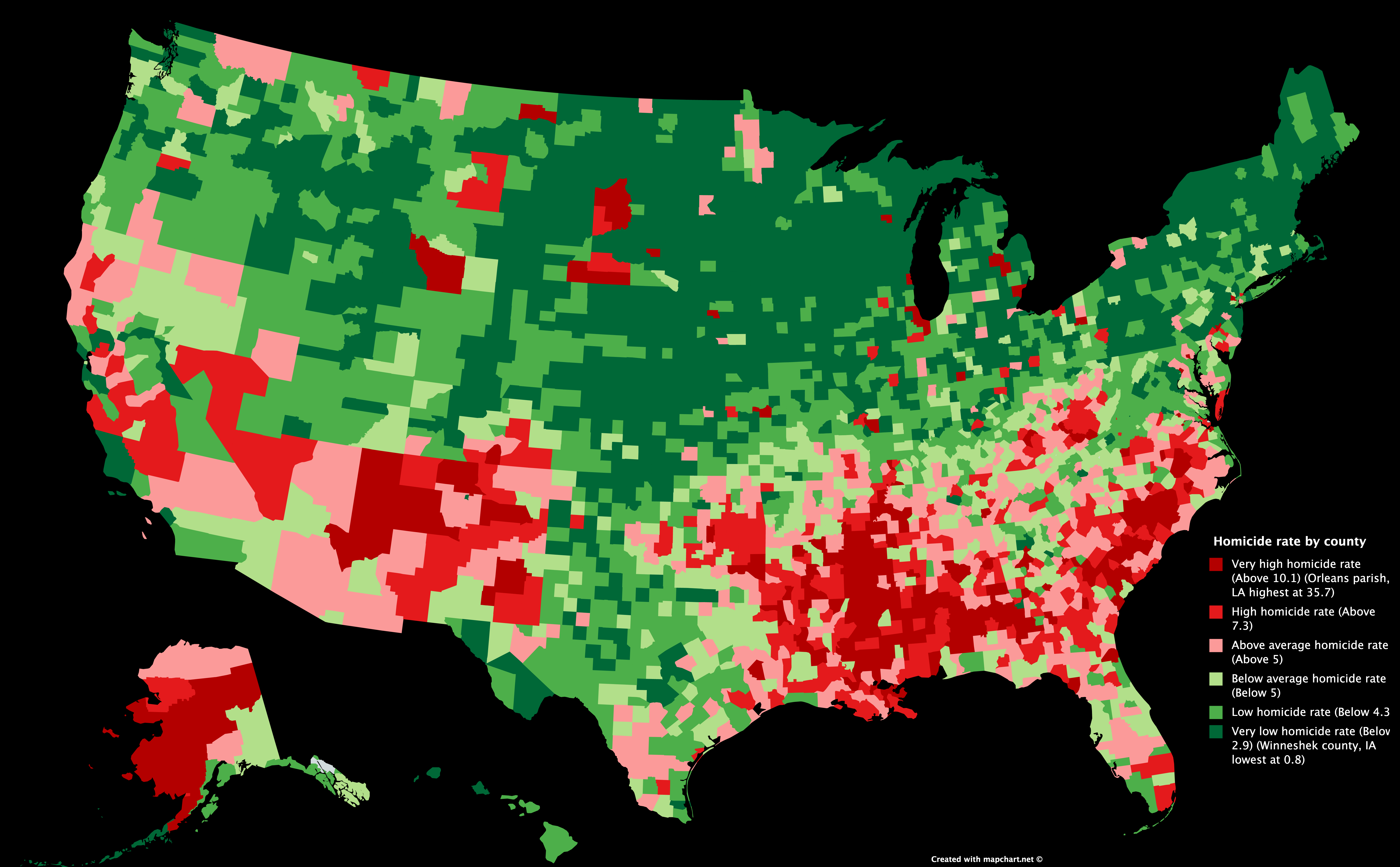

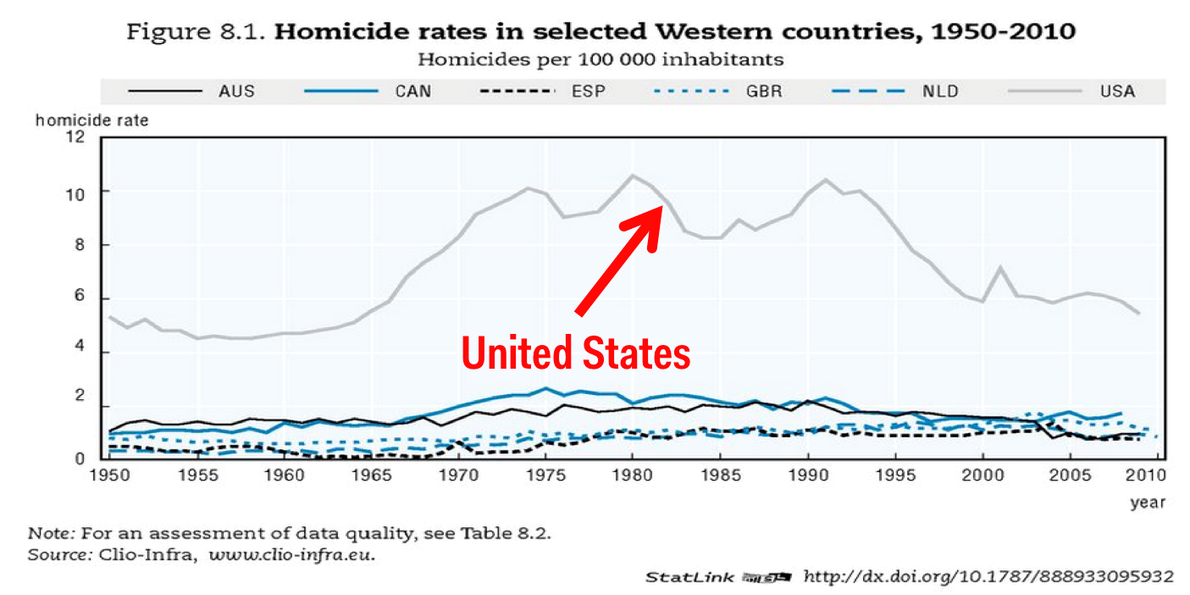

It is heartbreaking, near the end, to watch Dr. Lewis watch Attorney General Bill Barr on TV as he hands out federal executions like Oprah hands out cars for the first time since the federal government's last in 2003. (Timothy McVeigh's, by the way, which was attended by 200 onlookers, occurred in 2001.) "It's like watching one's work go down the toilet," she laments wistfully at age 82, her having convinced too few people across five decades that understanding the Why behind the What matters a great deal indeed if we are to ever predict or mitigate the number of murders occurring each year in any meaningful, systemic, institutional, sustainable way.

It saddens me, because she has such a huge heart and legitimately wants society to better understand why some people (overwhelmingly male) commit such heinous acts as cannibalism, or the other sorts of unspeakable horrors perpetrated by killers like Mark David Chapman, David Wilson, Marie Moore, Arthur Shawcross, and Ted Bundy.

Dr. Lewis is all for "locking 'em up and throwing away the key," on that point there is negligible debate, but she's also interested in rehabilitation and, more importantly, understanding violence in order to reduce its frequency and degree in future generations. Noble aims, to be sure, and ones any civilized society should pursue fervently. After all, there's nothing we can do about murder after the fact, so perhaps by understanding it we can also curb it through the identification of predisposing genetic markers, future medicines, surgeries, patches, implants, electroconvulsive therapies, educating and training parents and teachers, overhauling the justice system, etc. Nothing is off the table, I gather, except maybe for throwing warlocks into the water to see if they float.

In the near term, we remain at the usual impasses and deadlocks, none of which—to my way of thinking—should be misinterpreted as meaning that Dr. Lewis's work is wrong, useless, fruitless, or deserving of the toilet as she fears.

I think in the end, whatever the Why, what seems to matter greatly to victims' families is peace, and justice doesn't come in the form of three hots and a cot for 50 years upstate, it comes in the form of silence.

"Guns don't kill people, people kill people" the saying goes, but when a man fashions himself into a knife and kills vulnerable women and defenseless children with his bare hands over and over again, I understand victims' families wanting to see the steel of that human knife smelted to ash.

If it's science, there is no soul, and "We kill violent dogs—and people are worth more than dogs, right—so how is killing a murderous man any less humane?" one twice-attempted murderer asks Dr. Lewis earnestly, and it appears that many accept the logic of a madman as common sense.

p.s. Crazy, Not Insane is brought to you by Alex Gibney, the producer behind Going Clear: Scientology & the Prison of Belief and Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room.

And with that, I leave you with three thought-provoking charts: